About Food Waste

The Global Crisis of Food Waste

Food waste is a global challenge, with food loss and waste occurring throughout the entire supply chain. Food that is produced but not eaten ends up in landfills, creating methane—a powerful greenhouse gas that is a major contributor to climate change—meaning that reducing food loss and waste also reduces our greenhouse gas emissions. It is time to take action and make changes to Canada’s food system so that we can reduce food insecurity and our carbon footprint at the same time. There is a growing consensus globally that we need to address food loss and waste. Reducing food waste presents a real opportunity to tackle climate change in a way that’s easy, effective, and rewarding. Saving food from going to waste helps us make a real positive impact on the environment, and we can all do our part in minimizing food waste.

Substantially more than a third of food produced—possibly as much as 40%—is wasted globally, which is equivalent to:

2.5 Gt / year

Rate at which food is being wasted around the world:

80 000 kg/s

How much food people waste on average:

79 kg/person/yr

If all the wasted food were redistributed, it could provide the world each day with:

1.3 meals /

hungry person

Defining the Terms: Food Loss, Food Waste, & Surplus Food

Food Loss: Before the Store

Food loss refers to the decrease in quantity or quality of food resulting from decisions and actions by food suppliers, excluding retailers, food service providers, and consumers. It happens at an earlier stage in the supply chain—from harvest, slaughter, or catch, up to but excluding the retail level. This includes farming, production, processing, and storage, where factors like inadequate refrigeration, pests, diseases, or extreme weather can cause food to be discarded before ever reaching the retailer or consumer.

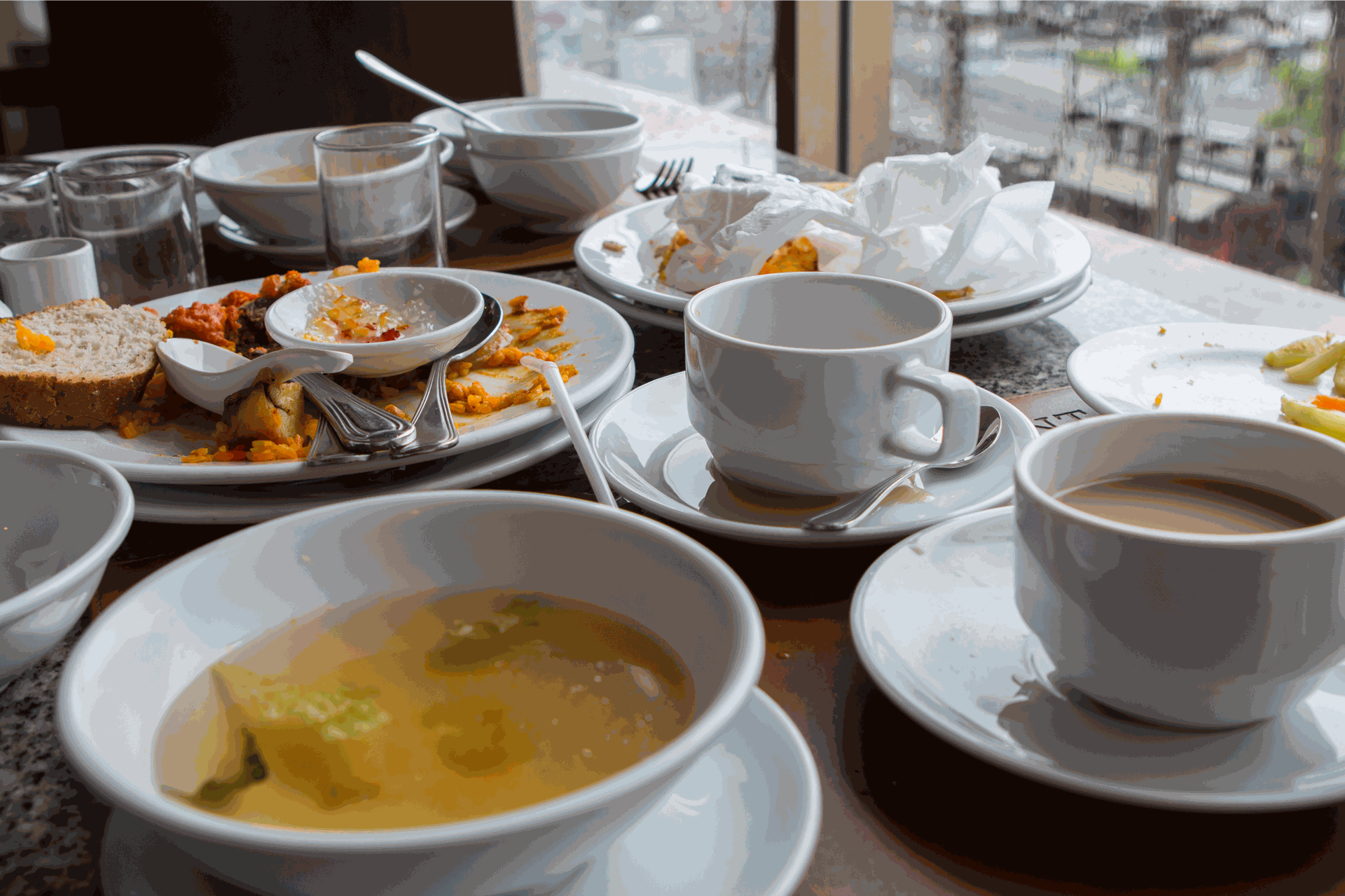

Food Waste: From Store to Table

Food waste refers to the decrease in quantity or quality resulting from decisions, behaviours, and actions by retailers, food service providers, and consumers. It specifically occurs once food reaches retailers, grocery stores, supermarkets, restaurants, hotels, schools, homes, and communities. Essentially, it refers to any food that remains uneaten at or after the retail and consumer stages—such as spoiled items in stores, leftover meals at home, or restaurant dishes that are never served.

Surplus Food

Surplus food is generated at any stage of the supply chain, from farm to fork. In most cases, it is perfectly good food that, for various reasons, is unlikely to be sold or consumed before its “best before” date—even though it has the same nutritional value as items on supermarket shelves. Although surplus food is not technically 'waste', it often ends up being discarded. Making the most of surplus food is a great way to reduce overall food waste, for example by redirecting surplus produce to charitable programs or rescuing surplus apples that are still perfectly edible but may not be sold for contractual or cosmetic reasons.

Where Food Waste Happens & Ends Up

Today, more food waste is being redirected away from landfills and toward more sustainable outlets like animal feed and composting. This shift is largely driven by environmental regulations, such as organic landfill bans that prohibit organic waste (like food scraps) from being sent to landfills. These bans help reduce methane emissions—a powerful greenhouse gas generated when food decomposes in landfills.

Repurposing food waste as animal feed is an increasingly popular solution. It allows food unsuitable for human consumption to be used effectively, reducing waste while also providing a cost-efficient feed option for livestock. Likewise, composting transforms organic waste into nutrient-rich soil, benefiting agriculture, landscaping, and gardening while also supporting soil health and waste reduction. Diverting food waste to these alternatives offers many advantages: it helps reduce disposal costs, creates potential revenue streams (such as selling compost or animal feed), improves brand perception, and ensures regulatory compliance.

However, only about 3.3% of avoidable food waste is currently rescued and redistributed. In fact, food rescue organizations are receiving slightly less food today than five years ago, as more businesses opt to divert food waste to composting or animal feed. This preference is often influenced by economic incentives and concerns around food safety, legal liability, and reputational risk. Despite these challenges, the benefits of food rescue and redistribution far outweigh the drawbacks. While redistribution can be more complex due to strict food safety requirements and the need for appropriate storage, it remains a powerful and impactful solution to both reduce waste and support communities facing food insecurity and/or hunger.

Why Does Food Waste Happen?

Strict Visual and Grading Standards

Retailers often set strict visual and quality standards—such as for texture, colour, size, and condition—that go beyond government regulations in order to appeal to consumer preferences. As a result, perfectly edible food is frequently discarded simply because it does not meet these aesthetic expectations. Edible food is regularly rejected due to cosmetic imperfections, even when it is safe and nutritious.

Produce is often discarded for failing to meet visual standards, and these rejections are largely driven by retailer specifications that exceed basic regulatory requirements. Such strict grading standards lead to the widespread disposal of good food, contributing significantly to overall food waste despite the food being entirely edible and of high nutritional value.

Confusion and Misunderstanding Around BBDs

Misunderstandings around BBDs are a major contributor to unnecessary food waste. Many consumers mistakenly interpret BBDs as expiry dates, leading them to throw out food that is still perfectly safe to eat. Unlike expiry dates—which apply to only five specific food types in Canada (meal replacements, nutritional supplements, infant formula, formulated liquid diets, and foods for low-calorie diets) and must be strictly followed—BBDs serve only as general guidelines for freshness, taste, and nutritional value.

This confusion leads to the disposal of perfectly good food, both at home and throughout the supply chain. In fact, BBD-related issues account for 23% of avoidable food waste from processing to the point of purchase. Misunderstood BBDs significantly contribute to unnecessary food waste and disposal across the entire food system.

Inadequate Storage and Inventory Management

Spoilage often occurs due to poor or improper refrigeration, storage, and inventory methods, causing products to become unusable before they can be consumed. When storage practices are inadequate and stock rotation is insufficient—such as failing to follow first-in, first-out methods—otherwise edible items can go bad prematurely. Ultimately, all of these poor storage and management approaches shorten the shelf life of food, and can result in significant spoilage and unnecessary waste throughout the supply chain.

Overstocking and Inefficient Ordering

Many food businesses overstock to avoid lost sales, but this often results in unused surplus going to waste. Excess inventory can spoil before it can be sold or consumed, and retailers frequently overorder to prevent running out of stock, which leads to further spoilage. Ultimately, overstocking—coupled with poor forecasting and ordering systems—contributes heavily to food waste.

Transportation and Cold Chain Failures

Issues in transportation and cold chain logistics are major contributors to the spoilage of perishable foods. Delays during shipping and improper temperature control can cause spoilage before food ever reaches its destination, leading to significant waste. Perishable items are especially vulnerable to timing and temperature fluctuations, and these breakdowns in logistics result in large volumes of otherwise edible food being discarded.

Climate Change and Extreme Weather

Changing climate conditions are making it harder for producers to grow and harvest consistent, market-ready crops. Difficult growing conditions increase waste, as changing weather patterns reduce crop consistency and lead to higher losses both pre- and post-harvest. Increased pest pressure, disease outbreaks, and extreme weather damage reduce yields and quality, causing further challenges throughout the supply chain. Overall, climate change leads to increased production challenges and greater food waste, as these unpredictable conditions and environmental stressors elevate pre- and post-harvest losses at the production level.

Human Error and Operational Challenges

Operational inefficiencies and human mistakes across production, transportation, handling, and distribution often lead to unnecessary food waste. Mistakes in processing, shipping, or stocking, as well as errors in labeling, storage, inventory management, or transportation, can cause the premature disposal of otherwise edible products. Inadequate staff training exacerbates these problems, resulting in mishandling, spoilage, and damage during transit. Altogether, mistakes in handling food throughout various supply chain stages—including improper storage, labeling, and transport—significantly increase the likelihood of waste.

Economic Factors and Market Conditions

Fluctuating market conditions and economic pressures can make food production and harvesting financially unviable. Low market prices often discourage harvesting altogether—especially when the potential profits don’t outweigh the cost of harvesting. In such cases, food may be left to rot in the field rather than be brought to market, resulting in significant food losses.

Market volatility and economic disincentives also discourage proper food waste management across the supply chain. When harvesting or distribution becomes economically unfeasible, edible food is frequently wasted. These financial barriers continue to play a major role in preventing the recovery and redistribution of surplus food.

The Impact of Food Waste

Food waste significantly harms the environment, climate, and biodiversity. When we talk about the environment, we refer to ecosystems, biodiversity, and natural processes happening around us. Climate encompasses the ambient state around us, including rain and weather patterns, temperature, and humidity—all of which are impacted by greenhouse gases being released into the atmosphere, trapping heat and warming the planet.

Food waste generates significant greenhouse gas emissions across the entire supply chain, contributing notably to climate change. Specifically, food waste accounts for 8-10% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. A key concern is methane (CH₄), a powerful greenhouse gas generated when food loss or waste is disposed of in landfills. Methane is 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide (CO₂), making it a major contributor to climate change. Reducing food loss and waste helps prevent methane generation, ensuring that energy, water, and land resources used in food production are not wasted.

When food is wasted, all the resources—such as water, energy, and labour—that went into producing it are also wasted. Valuable resources are unnecessarily consumed in producing food that ultimately goes unused. Wasted food unnecessarily uses large amounts of freshwater, land, and energy, resulting in an inefficient and unsustainable use of precious natural resources. Essentially, discarding food means discarding all the resources that supported its production.

Additionally, agriculture related to wasted food directly threatens ecosystems and biodiversity. Agricultural expansion driven by food production threatens biodiversity, damages soil health, and contributes to resource depletion. Consequently, food production and waste collectively cause significant biodiversity loss and ecosystem damage, negatively affecting the natural world around us.

Food waste has negative financial consequences for both businesses and consumers, contributing to broader affordability challenges and food inflation. For businesses, food waste leads directly to lost revenue due to financial losses incurred when purchased ingredients are wasted rather than sold or consumed. Operational expenses, including labour and resources for handling, storage, management, and disposal of wasted food, further increase these losses. Additionally, businesses face higher disposal costs and regulatory compliance expenses, including potential fines and penalties for producing excessive food waste and impacting the environment. Poor sustainability practices can also damage a company's reputation, reducing brand loyalty and sales as consumers become increasingly aware of and concerned about environmental issues.

Consumers and communities also feel the financial impacts of food waste, primarily through increased food prices and higher local taxes. Food businesses often raise prices to recoup losses associated with food waste, meaning that consumers indirectly bear these additional costs. Furthermore, municipalities, responsible for managing community waste, including food waste, incur significant expenses for waste collection, disposal, and recycling programs. These municipal costs, covered by taxes or local fees, typically rise with increased community food waste, placing further financial strain on consumers.

Overall, food waste exacerbates food inflation and affordability issues, making it increasingly difficult for consumers to access affordable food. Rising food prices and widespread food insecurity are partly driven by the financial burdens imposed throughout the supply chain by avoidable food waste, highlighting the critical economic importance of reducing waste at every stage.

Food waste directly contributes to increased food insecurity and hunger, affecting millions of people globally and locally. Millions suffer from hunger that wasted food could alleviate, yet millions of meals are missed because surplus edible food is not rescued and redistributed.

Every year, Canadians discard enough food to feed over 17 million people, yet only about 4% of Canada's surplus edible food is rescued for human consumption. This significant gap represents missed opportunities to address widespread food insecurity. Globally, redistributing edible food that is currently wasted could substantially reduce hunger, highlighting the critical social importance of rescuing and effectively redistributing surplus food to support those experiencing food insecurity.

Food waste is prevalent throughout Canada’s food system, spanning every stage from farm to fork. Alarmingly, 46.5% of all food in Canada is wasted annually, with 41.7% of this considered avoidable. Each year, 8.83 million tonnes of potentially edible food—valued at $58 billion—is wasted, enough to feed 17 million people. At the same time, nearly 1 in 4 people in Canada are food insecure, making these food waste statistics especially concerning. Recognizing the urgency of this issue, Canada has committed to reducing food waste by 50% by 2030 as part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (UN SDG) 12.3.

Food Waste in Canada:

Our Local Reality

The consequences of food waste in Canada go far beyond lost meals. Avoidable food waste generates 25.69 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions annually, equivalent to the yearly emissions from 5.6 million passenger vehicles. By reducing food waste, Canada has an opportunity to significantly lower its greenhouse gas emissions and thus environmental impact, while also realizing major financial benefits for both individual businesses and the economy at large.

Canada produces 3.2 million tonnes of surplus edible food each year—perfectly good food that is simply extra or unsold—and much of it could be saved from going to waste. However, 96% of this surplus is wasted rather than rescued, meaning only 4% is currently redirected to support individuals, communities, organizations, institutions, and facilities that need or could utilize these donations. These volumes of safe, edible food being discarded instead of donated represent a massive missed opportunity to reduce hunger and waste simultaneously, particularly in a country where food insecurity remains a persistent challenge.

Taking Action: Solutions and Opportunities

Reducing Food Waste Across the Supply Chain

In 2015, Canada committed to the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, specifically Sustainable Development Goal 12.3, which sets a target to halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains by 2030. Addressing food loss and waste at every stage—from production to consumption—can save Canadians money, enhance the competitiveness of the agri-food sector, and significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions. Key strategies include aligning production closely with demand, improving inventory management practices, and optimizing storage, ordering, transportation, and waste management methods, all of which boost economic efficiency and environmental sustainability.

Rescuing Surplus Edible Food: A Win-Win Approach

One of the most impactful steps to reduce food waste involves redirecting surplus edible food toward food rescue organizations, charities, nonprofits, social programs, community groups, and community centres. This approach not only supports individuals and families facing food insecurity but also substantially reduces greenhouse gas emissions—far more effectively than composting. Donating surplus food thus delivers dual benefits: improving local community well-being and protecting the environment.

Benefits for Businesses, Communities, and Charities

Reducing food waste yields significant advantages across multiple stakeholders. For businesses, proactively minimizing food waste can decrease disposal costs, generate additional revenue or savings through productive use of surplus food, and enhance their public image by meeting consumer expectations around sustainability. Improved sustainability practices foster customer loyalty and consumer trust.

For communities and charities, the advantages of food rescue extend beyond environmental benefits by providing greater access to fresh, nutritious food, directly benefiting families and individuals in need as well as the groups, programs, organizations, and institutions that could use the rescued food to support their own staff and/or volunteers. This dual-impact approach thus addresses both food insecurity and environmental challenges, ensuring donors are contributing meaningfully to community welfare and sustainability efforts through the food resources that they are donating.

Policy Changes and Industry Incentives

Policy reforms and economic incentives are crucial to effectively tackling food waste. Targeted economic measures encourage businesses to invest in waste reduction and improve operational efficiency, incentivizing surplus food donations rather than disposal. Regulatory frameworks, including landfill bans and stricter compliance requirements, further motivate waste reduction and discourage wasteful practices. Public policies explicitly designed to support food rescue and recovery initiatives can significantly lower food waste levels across all sectors.

Empowering Consumers Through Education and Action

Consumer awareness and individual actions are central to the fight against food waste. Education campaigns should clearly differentiate between best-before dates and expiry dates, encourage consumers to embrace imperfect-looking produce, and promote sustainable shopping habits. Understanding that “best before” doesn't mean “bad after” can greatly reduce unnecessary household waste. Individuals can also make a meaningful impact through informed purchasing decisions, proper food storage, creative use of leftovers, and effective meal planning. By adopting sustainable habits at home, consumers become active participants in reducing food waste, directly contributing to positive environmental and social outcomes—right from their kitchens.